Author: Erin Warner

Dusk settles over Robertson Millpond Preserve. Eight biologists, interns and volunteers rest on the hot parking lot pavement, scarfing sandwiches in the final moments before the bat nets open at 8 p.m. They’ve spent the past five hours wrestling 24-foot poles into the swamp floor, raising nets, and blocking flight pathways.

Survey crew forecasts the night

Dr. Rada Petric, Research Assistant Professor at UNC Chapel Hill, breaks the quiet with a challenge.

“We’re going to play a game… How many bats are we going to catch tonight? And how many species?”

At this location, there’s potential for six species. When the site was last surveyed in 2023, only seven bats spanning three species were captured: big brown, evening and eastern red bats.

Sara Grace, an N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) intern, offers her guess. “Four species. Thirteen bats.”

NCWRC Conservation Coordinator Olivia Munzer counters: “Three species. Ten bats.”

Intern Ren pipes up, “I just want to see a tricolored bat!”

The tricolored bat is state listed as endangered in North Carolina and notoriously hard to catch. At the Preserve, the last confirmed capture dates back to 2019, highlighting just how rare detections are in the area.

Bat data leads to conservation

Collecting data here lays vital groundwork for bat conservation. Reliable information guides monitoring procedures, shapes research strategies, and ensures the right management actions are taken for vulnerable, state listed species.

“Our role is gathering data to understand species population trends and distributions, so we can better manage and conserve populations,” says NCWRC Wildlife Diversity Biologist Katherine Etchison.

Bats capture by region

According to NCWRC Wildlife Diversity Technician Ellen Pierce, the regional variation in bat capture is stark. “On the coast of North Carolina, we easily catch 30 bats a night. In the mountains, we are lucky to get double digits. Here, in Central Piedmont, it’s hit or miss. This year, our surveys have ranged from catching one to 11 bats.”

Hardest survey site of the Piedmont

Robertson Millpond is considered the most challenging site Olivia has surveyed in the Piedmont region. Three of the five nets sit deep in the swamp, only accessible in waders. Technicians must slog through waist-deep water, freeing their boots from the suction of mud with every step. A kayak serves as a water taxi, ferrying gear and staff to the farthest net stations.

Why Robertson Millpond Preserve?

The team’s effort is part of a larger collaboration with the North American Bat Monitoring Program (NABat). Acoustic recordings collected by Dr. Han Li suggested the possible presence of northern long-eared bats. While none were captured, the swamp is ideal for tricolored bat habitat, and previous surveys have confirmed their presence.

How to catch a bat

Over time, the team has refined their netting strategy. A newly installed walking path to the Preserve’s fishing pier altered forest dynamics, pushing bats into different flight corridors.

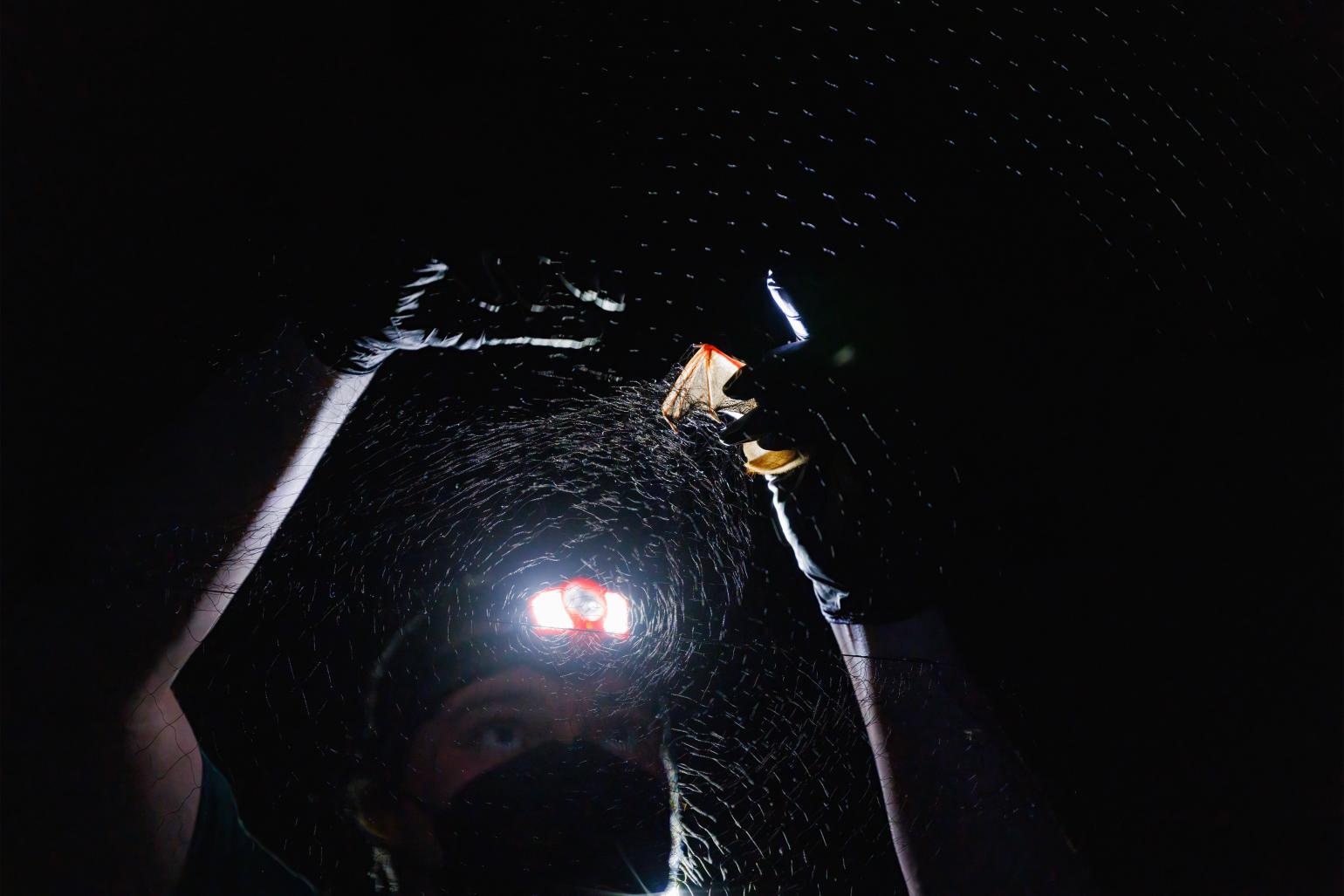

In response, the crew repositioned two nets to intersect the paved path, while three others were arranged in a U‑shape across the open swamp. The idea is simple: dense cypress and low canopy vegetation should funnel any bat that avoids the first net into one of the two adjacent nets. In past seasons, they experimented with a box layout, but each year they test new formations to optimize capture.

“It’s not an ideal situation because it’s such an open area. But it works with these juvenile tricolored. They just aren’t quick enough to turn around,” says Olivia.

Animal versus human welfare

Rada emphasizes the team’s commitment, stating, “Animal welfare is our No. 1 priority.”

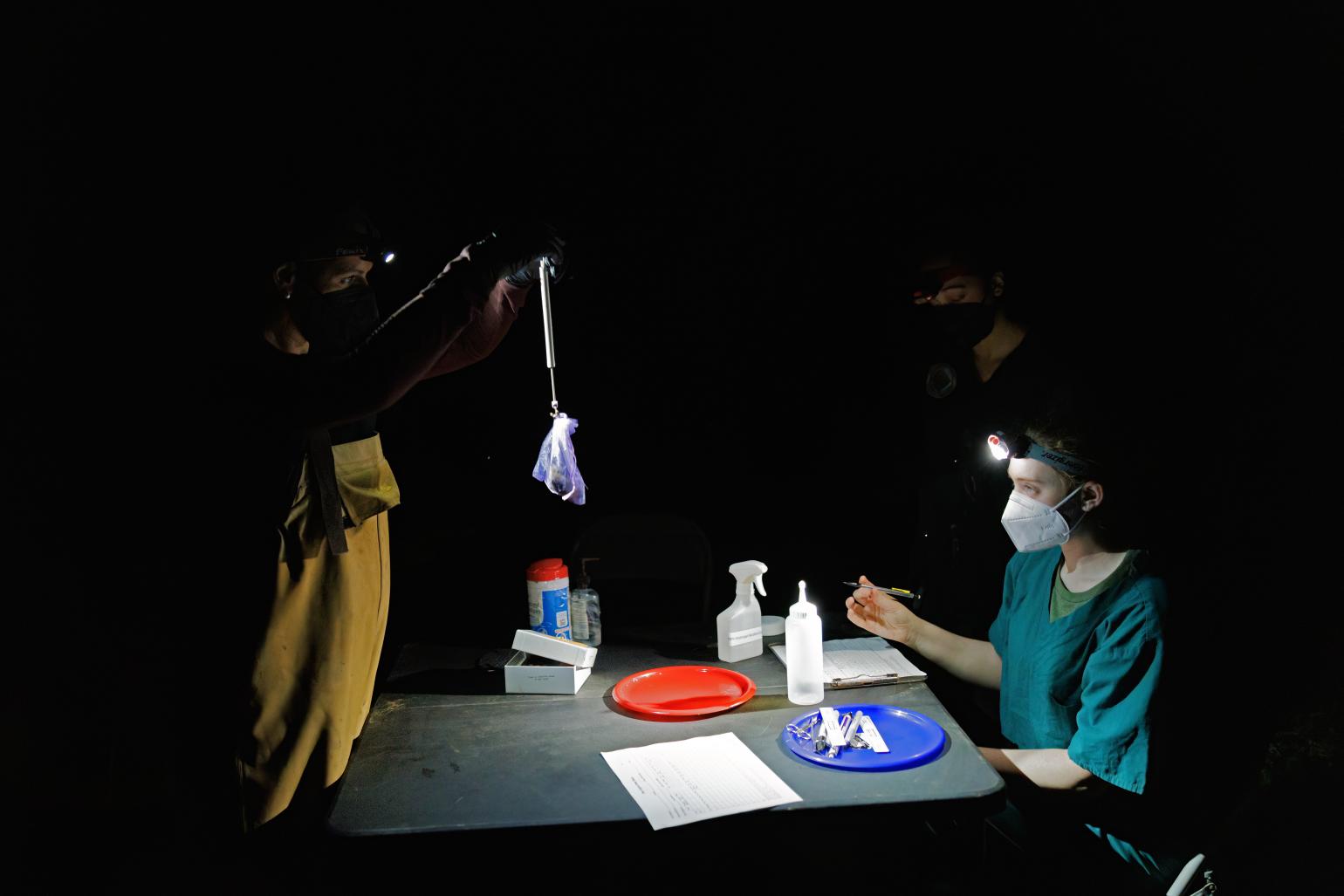

Nets are checked every eight minutes, and bats are released within 20 minutes to minimize stress. Handlers wear scrubs, masks, and leather gloves when inspecting the specimens.

The same cannot be said for human welfare. The Preserve is filled with hazards like poison ivy, biting ants, and cypress knees, perfect for tripping over in the dark. As Olivia lifts her arm to examine the net, red bug bites speckle her skin. They are the battle scars of a biologist. Yet excitement builds as bats begin to circle overhead.

The first tricolored bat in six years

Silhouetted against the darkening sky, the bats swoop with agility.

“Wow, they are so smart!” marvels Rada as two deftly evade the netting.

When a bat strikes net No. 3 in the swamp, UNC student Annalise cries out, “Bat!”

Olivia, a trained bat handler, rushes through the murky water to extract the captured animal. It’s not just any bat, but a rare tricolored bat, the first this crew has found at the Preserve in six years. Tricolored bats are no bigger than three inches. Entangled in the netting, its tiny wings supported by bones as thin as toothpicks must be handled with extreme care.

Olivia tucks the bat into a mesh bag and carries it out to a clearing by the data table. When she removes it, she supports its body with one hand and uses her thumb and forefinger to gently immobilize the body.

Key data is recorded: sex, age, weight, reproductive status, and signs of White-Nose Syndrome, a devastating disease affecting bat populations in North Carolina’s mountains and the Piedmont region.

The bat range map expands

Earlier this season, the crew netted the first recorded tricolored bat on Vance County Game Lands. This endangered bat is more than a local discovery; it’s a piece in a much larger puzzle.

Wildlife officials rely on field data to update species distribution maps, helping researchers, land managers, and the public understand where these bats live and move. Although the tricolored bat is documented statewide, its true range remains uncertain in unsurveyed areas.

“For me as both a bat biologist and habitat conservation coordinator, I find it important in having a more accurate range map,” says Olivia. So, she and her crew are working diligently to fill gaps.

A lack of records doesn’t prove absence; only a survey can confirm whether a species is present. With bats traveling up to five miles a night, there is no telling what more data collection could uncover!

Top bat priorities

New data not only impacts range maps but also guides bat-specific strategies for the next decade in the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plan (SWAP). Some top priority conservation actions include:

- Establish new survey sites impacted by extreme weather to assess the effects on wildlife.

- Examine winter behavior of bats in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain.

- Prioritize surveys of bat species most impacted by White-Nose Syndrome (WNS).

- Protect bat roosting sites for all priority bat species, particularly those that are known roost sites for species affected by WNS.

- Support volunteer efforts such as NABat survey routes to monitor species and habitat.

- Monitor bats statewide with capture, roost, hibernacula, and acoustic methods.

Bat surveys become real tools of conservation, making sure those tiny, endangered flyers get a fair chance at survival.

Total bat tally

By the end of the night, the team had successfully captured 14 bats across four species, including two tricolored bats. But for the crew from NCWRC, UNC Chapel Hill, and Wake County Parks, Recreation, and Open Spaces, it was more than just a data collection effort. It was a shared commitment to the conservation of bat populations.